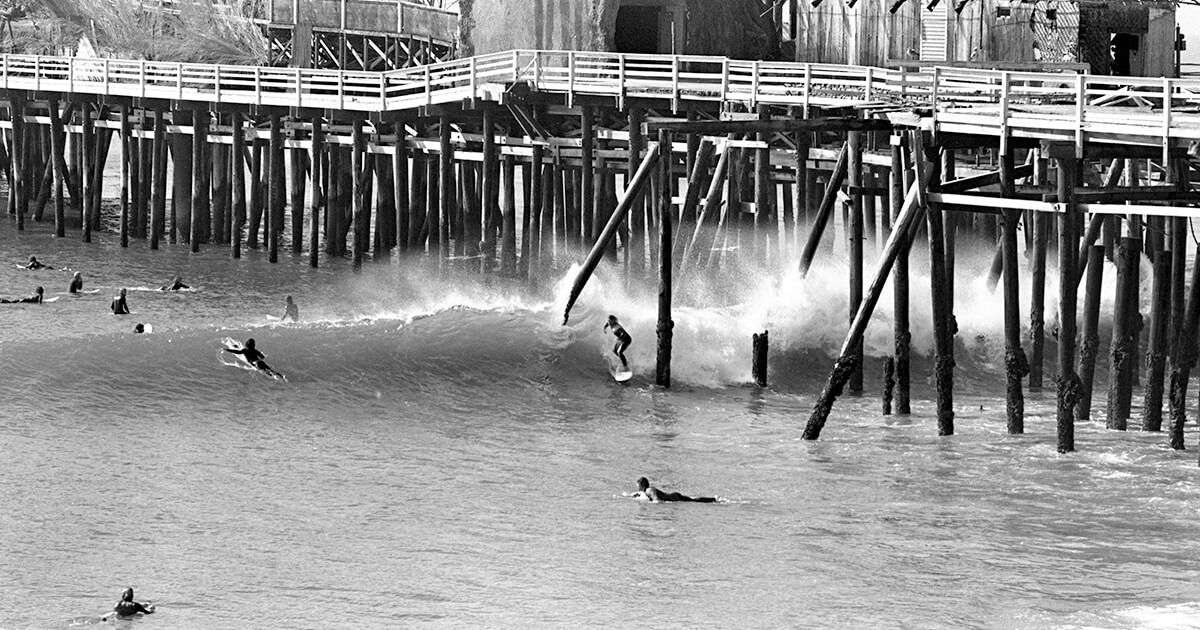

To mark the 20th anniversary of his landmark film on the birth of modern skateboarding, Dogtown & Z Boys (2001), the award-winning director and legendary skateboarder drops in for a deep-dive into documentary.

SPLENDOID: Where did the idea for the film come from, was it a story that you were interested in telling or, being a core member of the Z Boys yourself, did the film find you?

PERALTA: It was an idea that was tucked into the far reaches of my brain. I knew the story could make a good film but I didn’t know if the chance to make it would ever occur.

I always put forward Dogtown as being an epitome of modern documentary in that it throws all possible filmmaking techniques and principles into a pot but, far from the end result being a mess, the sum of the parts is totally appropriate to the subject matter making the film feel very truthful and authentic. Could you expand on that a bit more?

I wanted the construction and tone of the film to feel like the subject matter itself: raw, gritty, messy, imperfect, a bit subversive, and with deliberate mistakes included in the production. But also, I wanted there to be a beating heart with good characters and good story telling. Most importantly I wanted the film to be inclusive – meaning that I wanted viewers to feel welcome to enter this world. I try to use this approach and technique in all of my films. I really want the look and feel to be a reflection of the subject matter.

Did you have a set methodology as to how you approached making the film?

I always begin with trying to get the look, sound, tone and feel of the film I’m hoping to make. In the early stages of production all of these aspects are merely impressions in my head that I am trying to get a feeling of. It’s like trying to recollect a dream, piecing together all of the impressions and fragments that you can remember until it somehow becomes whole.

One signature of the film, all of your films actually, is the very expressive editing. Do you have your various techniques in mind before you start, or do you design them going along, according to the material that you were capturing?

Some ideas you begin with and many you get during the process. During production of a film, if you are doing the right thing as a film maker and you are listening carefully and paying careful attention – at some point the film will tell you what it wants. When that happens you become it’s servant. To me that is the highest state to achieve as an artist, when you are able to get out of the way and let the film take on it’s own life.

I imagine the emergence of new filmmaking technologies played a big part?

I consider the editors I work with as being more like composers because of how the equipment allows them to work – the move to digital post-production really took the constraints off and allowed them to soar. It became so easy to do so many complex things – multiple dissolves, multiple music tracks, 3D graphics – all at the stroke of a single key. On the other hand, the new tools have done nothing to thwart the proliferation of bad movies produced year after year.

When you start a new project do you already have an idea of the mode of exhibition?

My goal from the start is to premier at Sundance, and then get theatrical distribution.

How are subjects for your films chosen?

Subjects that are gnawing at my brain so relentlessly that I am willing to devote two to three years of my life unravelling them into a film.

What is the promotion/distribution model that you follow? Is it standardised or bespoke for each production?

My films have no “stars” or “name actors” in them. As a result the film distribution companies that have handled my films require me to go on the road for about six months promoting my film; showing my film at festivals, doing countless interviews on radio, TV, internet, newspaper, magazines, photo sessions etc. I calculated that I do about six hundred interviews for each film that i have made.

I’m required to talk so much about my films to so many people in such a concentrated amount of time that I get to the point where I can’t stand hearing myself speak anymore. But it’s necessary because the indy distributors don’t typically spend large amounts of money advertising or marketing doc films – so they rely on us, the film makers, to get the message out.

At some point the film will tell you what it wants. When that happens you become it’s servant

Do you create films that cater for an audience or market or are you more concerned with creating the work how you would like it to be and then hope people like it?

I make films that I would want to see about subjects I’m interested spending time with. Who the audience is comes last. Also, if I thought about an audience prior to making my films then I probably would never have embarked on any of them.

Are there any constraints on your work – i.e. do you have trouble raising finance, do your particular working methods make it difficult to crew up…?

Obtaining finance is always a challenge and always will remain a challenge. At best it usually takes a year or two. At worst it can take an extraordinary amount of time, enough time to wear you out. It has become more difficult in today’s climate.

I am interested by the fact that Vans financed the Dogtown project, did that have any influence on the filmmaking process?

They asked us to get the film done on time and on budget. They never once asked to see a rough cut of any kind nor did they ever offer us notes or suggestions, nor did they ever ask us to listen to their point of view. They were the greatest client that I’ve ever worked with.

Perhaps that is because they are really more than just financiers. It must be a bit unusual that the people putting up the money are also a core component of the story being told?

They were interested in taking a pro-active part in the presentation of our shared history. They took a chance on this film as they, and us, never expected the film to be successful. We were caught off guard when we were accepted into Sundance, and again when we obtained an international distribution deal with Sony Classics. None of us ever thought the film had a chance because we didn’t think people would be interested in the subject matter. The whole thing was really an experiment.

Broadening our scope a bit, at the time of its release Dogtown was often said to be part of a new wave/sub-genre of documentary, one that was giving factual filmmaking a reboot by taking a more cinematic approach. In your opinion, does this new-wave actually exist or are modern films simply a contemporary form of the kind of creative factual films that have always been made, I’m thinking particularly of the Lumière brothers, Grierson, Vertov, et al. Perhaps the only difference is that creative docs are now in vogue?

I think its fair to say that it does exist and that, actually, it has always existed. We are just seeing a rise in the popularity of that kind of documentary right now. But we are also seeing a proliferation in media distribution outlets that did not exist before. There are more specialised television channels now than there have ever been and there are so many unique platforms to view films on and more coming online every year. As a result, there is a huge need for new product.

Could I ask you about films like Fahrenheit 9/11; March of the Penguins; Supersize me; or Capturing the Friedmans. They are now seen as classics of documentary and all came out roughly around the time of Dogtown, do you feel that they have anything in common?

One of the problems with documentaries is that every doc film is categorised under the same banner, whereas with feature films you have comedies, dramas, thrillers, action-adventure, romantic comedy, etc. Even though my films are radically different than say March of the Penguins or Supersize Me yet they fall under the same heading. This categorisation boxes us in as filmmakers and it boxes in the entire medium of documentary films. We are all classified as being one type when in fact we are all so different.

But what would you say is responsible for docs to now be so popular?

Some say content is King. I believe context is King.

Is it perhaps just the way that they are being marketed, meaning that they have campaigns similar to entertainment product?

Watching doc films doesn’t have to be like eating spinach! These films aren’t science experiments. They are entertainment product. Just because they might be documenting a serious subject doesn’t mean they can’t be pleasing, compelling, or enjoyable to watch.

Then could it be that they being specifically constructed so that they can be sold easily, they have strong ‘hero’ characters, they cover ‘big’ subjects with easy-to-follow narrative arcs etc?

I don’t think so. They are constructed by filmmakers who have something to say. If these filmmakers have a way to make their films more palatable to the public then more of the public will most probably go to see their films and thus be affected by the subject matter.

Look at Michael Moore – with Sicko he took a very important but deadly boring subject and made it entertaining, compelling, and thought provoking. He made a film that got millions of Americans to think about and talk about national healthcare issues. You may not agree with his point of view but what he does takes extraordinary talent.

It does indeed. Going further, Moore’s films very much carry his individual style, the mark of an auteur, we might say. Is it more possible to stamp your mark on a cinema-released film than one created for TV?

Probably so. It takes a filmmaker with style and vision to make a film that rises to the level of an international theatrical release. An international deal is the Holy Grail to filmmakers and it’s very tough to achieve and there are only so many available slots per year. It’s much easier to get a run on television.

So, could it then be that filmmakers today have to mixing traditional observational techniques with elements of flamboyant showmanship in order to circumvent potential distribution problems?

Documentary films are competing on the open market against the largest “tent pole” fiction films. Franchises like Batman, Spiderman, etc are gigantic films with gigantic budgets and gigantic advertising and marketing campaigns behind them. It is our job as documentarians to make compelling films and to tell compelling stories. Scoring our films with great music or painting our films with cutting-edge graphics and treatments does not diminish the integrity of our stories.

Meaning that they create a kind of ‘subjective truth,’ a way of telling authentic stories and engaging the audience?

The great David McCullough once said that that the non-fiction writer has to craft his stories to read like the best fiction. I put a tremendous amount of thought into figuring out how to make my work entertaining, compelling and enjoyable especially when it comes to presenting dry passages of solid information, back story, or historical passages pertinent to the narrative.

As a filmmaker telling true stories I am always confronted with the task of including information in my films that could be considered by many to be necessary but flat. My job is to figure out a creative way of presenting this information so that it doesn’t interrupt the flow of the narrative and I don’t lose people’s attention but instead engage them, provoke them, interest them.

Do you think it is possible to define a set of stylistic rules that could be used to construct a film that would automatically be considered a ‘new wave’ documentary?

There should be no rules. And any rules that are implemented should be broken. Rules impose boundaries and boundaries can cause terrible damage to the creative process.

Sometimes being too intellectual can take you out of the feeling and out of the heart of a project

Taking that last remark into account, I am interested to know if you are aware of the 6 modes of documentary, as suggested by the critic and theorist Bill Nichols?

No idea. I’m self-taught.

OK. Well, Nichols published quite a landmark text in 1991, Introduction to Documentary, in which he posited the existence of 6 modes, or ways in which docs are made, and how they demand our attention. To run through them quickly, they are; ‘poetic,’ ‘expository,’ ‘observational,’ ‘interactive,’ ‘reflexive,’ and ‘performative’…

Actually, I have an issue with this topic. It feels too intellectual and textbook-like. Sometimes being too intellectual can take you out of the feeling and out of the heart of a project.

I do agree with you to an extent but, equally, I think they are helpful when applied after the fact to help us understand a film better. For example, in a comparison between a ‘traditional’ documentary film that uses the expository mode and a piece of ‘direct cinema’ employing a pure usage of the ‘observational’ mode, would you consider the second, with its apparently unmediated style, to be the more truthful?

I think that they can co-exist. A film could have both a rigid observational approach and be heavily stylised. You don’t have to lose one for the other. Look at all of the feature films that are based on true stories; to take an obvious example, Schindler’s List, it is hugely stylised yet is rooted in truth. There is no reason that documentary film makers should be forced to follow a one-size-fits-all category.

And what’s your personal view on the growth in popularity of documentary?

I love it, and I love being a part of this group of filmmakers.

And a final self-indulgent question – I have always felt that your work on the Powell-Peralta videos set up an aesthetic which was perfect for board-sports films. The success of films like Ban This or Animal Chin meant that this style started to become vernacular for many alternative cultures to represent themselves and be represented across mainstream media. Would you agree with that?

I guess a case could be made for it. I certainly didn’t think at the time that I was doing something that would have any kind of lasting effect.